Parenting Hacks: Understanding Twice-exceptional Students | Understanding Giftedness | HKAGE

Teaching gifted students is already a challenge for many educators and parents. However, when these gifted students not only possess exceptional qualities different from typical students but also have some learning difficulties, providing appropriate support becomes crucial. Failure to address these learning difficulties can become a significant obstacle for gifted students to unleash their talents.

Categories and Characteristics of Twice-exceptional Students

According to the Operation Guide on the Whole School Approach to Integrated Education updated by the Education Bureau of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government in 2019, twice-exceptional students are not classified as a separate category of special education needs. Instead, they refer to individuals who have both exceptional intellectual abilities and one or more special education needs. When gifted students have multiple learning difficulties, they are referred to as multiple-exceptional students.

- Learning Needs: Special learning difficulties, such as dyslexia.

- Behavioural, Emotional, and Social Developmental Needs: Difficulties with attention, self-control, or social development, such as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism.

- Sensory, Communication, and Physical Needs: Sensory impairments, such as visual impairment or hearing impairment; communication difficulties, such as speech disorders; motor activity disorders, such as cerebral palsy.

The specific learning difficulties can include one or more of the following:

Learning Disorder | Communication Disorder |

Reading Disorder | Expressive Language Disorder |

Dyscalculia | Mixed Receptive-Expressive Language Disorder |

Disorder of written expression | Phonological disorder |

Motor skill disorder | Stuttering |

Developmental coordination disorder |

|

Challenges in Identifying Twice-exceptional Students

Identifying twice-exceptional students is not easy because their abstract reasoning abilities can mask their weaknesses. The more intelligent a child is, the more difficult it becomes to identify their learning difficulties (Silverman, 2002). Similarly, the exceptional intelligence or talent of twice-exceptional students can be overshadowed by their learning difficulties. The identification process generally focuses on either nurturing their gifted qualities or addressing their special education needs separately (Boodoo, Bradley, Frontera, Pitts & Wright, 1989). Additionally, some twice-exceptional students may go unnoticed and unclassified, receiving no support in any category because they appear no different from typical students.

3 situations commonly encountered by Twice-exceptional Students in schools:

Situation 1

Teachers focus solely on developing their giftedness without identifying their learning difficulties. As the learning materials become more complex, their academic performance may decline steadily, leading to a decrease in their motivation and self-doubt about their abilities (Baum & Owen, 2004). They often become underachieving or disengaged students and may even be labelled as "lazy" (Silverman, 1993). If the students' learning difficulties are not identified by high school, social and emotional problems may grow together with their learning difficulties (Baum & Owen, 2004).

Situation 2

They are only provided with support for their special education needs while their talents continue to be overlooked. The intense helplessness associated with their learning difficulties gradually overshadows any positive feelings related to their exceptional talents, and the education system reinforces their negative feelings (Baum & Owen, 2004).

Situation 3

As for those twice-exceptional students who remain unclassified, their higher cognitive abilities compensate for their learning difficulties, enabling them to maintain academic performance at an average level without fully realising their potential. As a result, they are not identified or referred to gifted programmes or special education services (Trail, 2011).

Intelligence hides the disabilities, while the disabilities mask the talents. Sometimes, in non-traditional learning environments, such as reducing written reports and utilising drama, debates, projects, and discussions, their talents can shine (Baum & Owen, 2004).

Prominent Individuals with Disabilities

1) Researching Prominent Individuals with Disabilities

Understanding prominent individuals with disabilities can help twice-exceptional students and their families recognise that despite facing disabilities, they can still achieve success. When selecting role models, it is important to guide twice-exceptional students in choosing individuals with similar disabilities, but without explicitly mentioning their disabilities. It would be better if children discover their disabilities through their own research. (Trail, 2011)

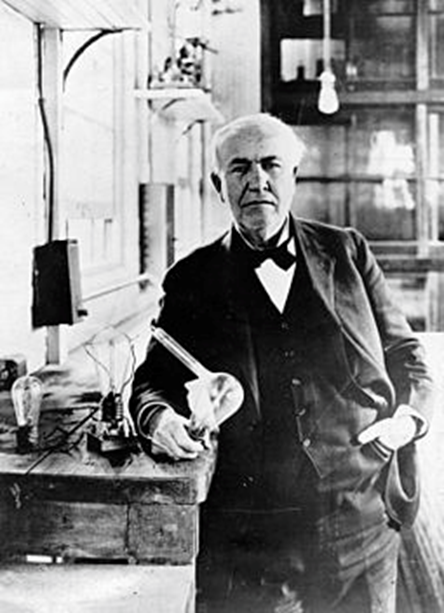

Prominent Individuals with Disabilities - Thomas Edison (Hearing impairment)

Prominent Individuals with Disabilities - Thomas Edison (Hearing impairment)

Prominent Individuals with Disabilities - Walt Disney (Learning disability)

Prominent Individuals with Disabilities - Walt Disney (Learning disability)

2) Prominent Individuals with Disabilities

Disability | Prominent Individuals | Outstanding Achievements |

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | Tim Page Temple Grandin Ko Wen-je | Pulitzer Prize-winner, Critic, Writer College professor, Author Doctor, Politician |

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) | Michael Phelps Richard Branson | Olympic swimming champion Entrepreneur

|

Learning Disability | Albert Einstein Henry Winkler

Lee Kuan Yew | Mathematician, Physicist Actor, Writer Lawyer, First Prime Minister of Singapore |

Others | Stevie Wonder (Visual impairment) Thomas Edison (Hearing impairment) Walt Disney (Learning disability) | Singer, Composer Inventor Producer, Entrepreneur |

---------------------------------------

References:

- Baum, S., Olenchak, F. R., & Owen, S. V. (1998). Gifted students with attention deficits: Fact and/or fiction? Or, can we see the forest for the trees? Gifted Child Quarterly, 42(2), 96-104.

- Baum, S., & Olenchak, F. R. (2002). The alphabet children: GT, ADHD and more. Exceptionality, 10(2),77-91.

- Baum, S., & Owen, S. V. (1988). High ability/learning disabled students: How are they different? GiftedChild Quarterly, 32, 321-326.

- Baum, S. M. & Owen, S. V. (2004). To be gifted & learning disabled: Strategies for helping brightstudents with learning & attention difficulties. Mansfield, CT: Creative Learning Press.

- Bender, W. N. (2008). Differentiating instructions for students with learning disabilities: Best teachingpractices for general and special educators (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Bianco, M. (2005). The effects of disability labels on special education and general education teachers'referrals for gifted programs. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 28, 285-294.

- Boodoo, G. M., Bradley, C. L., Frontera, R. L., Pitts, J. R., & Wright, L. P. (1989). A survey of proceduresused for identifying gifted learning disabled children. Gifted Child Quarterly, 33(3), 110-114.

- Brody, L. E., & Mills, C. J. (1997). Gifted children with learning disabilities: A review of the issues. Journalof Learning Disabilities, 30, 282-297.

- Coleman, M. R. (2005). Academic strategies that work or gifted students with learning disabilities.Teaching Exceptional Children, 38(1), 28-32.

- Cooper-Kahn, J. (2011). Developing executive skills in gifted children. Nurturing the Gifted, 5, 6-9.

- Cooper-Kahn, J., & Dietzel, L. (2008). Late, lost, and unprepared: A parents'guide to helping childrenwith executive functioning. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House.

- Dawson, P., & Guare, R. (2004). Executive skills in children and adolescents. A practical guide toassessment and intervention. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Dawson, P., & Guare, R. (2009). Smart but scattered. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Gillberg, I. C., & Gillberg, C. (1989). Asperger syndrome - Some epidemiological considerations: Aresearch note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 30, 631-638.

- Graner, P. S., Faggella-Luby, M. N., & Fritschmann, N. S. (2005). An overview of responsiveness to intervention: What practitioners ought to know. Topics in Language Disorders, 25(2), 93-105.27 -

- Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Guy, S. C., & Kenworthy, L. (2000). Behavior Rating Inventory of ExecutiveFunction. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Hartmann, T. (1996). Beyond ADD: Hunting for reasons in the past and present. Green Valley, CA:Underwood Books.

- Henderson, A., Johnson, V., Mapp, K., & Davies, D. (2006). Beyond the bake sale: The essential guide tofamily/school partnerships. New York, NY: The New Press.

- Hishinuma, E., & Tadaki, S. (1996). Addressing diversity of the gifted/at risk: Characteristics foridentification. Gifted Child Today, 19(5), 20-25, 28-29, 45, 50.

- Lovecky, D. V. (1999, October). Gifted children with AD/HD. Paper presented at the 11th Annual CHADD International Conference, Washington, DC.

- Lovecky, D. V. (2004). Different Minds: Gifted Children With AD/HD, Asperger Syndrome, and OtherLearning Deficits. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- MacMillan, D. L., & Siperstein, G. N. (2002). Learning disabilities as operationally defined by schools. In R. Bradley, L. Danielson, & D. P. Hallahan (Eds.), Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice (pp. 287-333). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- McCoach, D. B., Kehle, T. J., Bray, M. A., & Siegle, D. (2001). Best practices in the identification of gifted students with learning disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 38, 403-411.

- McCoach, D. B., Kehle, T. J., Bray, M. A., & Siegle, D. (2004). The identification of gifted students with learning disabilities: Challenging, controversies, and promising practices. In T. M. Newman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Students with both gifts and learning disabilities (pp. 31-48). New York, NY:Kluwer.

- Nielsen, M. E. (2002). Gifted students with learning disabilities: Recommendations for identification andprogramming. Exceptionality, 10, 93-111.

- Neihart, M. (2000). Gifted children with Asperger's Syndrome. Gifted Child Quarterly, 44, 222-230.

- Sternberg, R. J., & Zhang, L. F., (2001). Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles. Mahwah,NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Sternberg, R. J., Grigorenko, E. L., & Zhang, L. F. (2008). Styles of learning and thinking matter ininstruction and assessment. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 486-506.

- Silverman, L. K. (1993). Counseling the gifted and talented. Denver, CO: Love.

- Silverman, L. K. (2002). Upside-Down brilliance. The visual-spatial learners. Denver, CO: DeLeon Publishing.

- Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners.Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Trail, B. A. (2011). Twice-exceptional gifted children: Understanding, teaching and counseling gifted students. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.28 -

- Webb, J. T., Amend, E. R., Webb, N. E., Goerss, J., Beljan, P., & Olenchak, R. (2005). Misdiagnosis and dual diagnoses of gifted children and adults: ADHD bipolar, OCD, Asperger's, depression andother disorders. Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press.

- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. In T. M. Cole (Ed.), Mind in society(pp. 79 – 91). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.